American artefacts

As one of our project members is currently undertaking a research trip to the US (and UK), I thought that for this week’s blog, I might pull out some of my favourite American artefacts from the Christchurch collection. While British products and British-made materials (like glass and ceramic) are most common on nineteenth century European sites, we do find some items from the USA. Almost all of these are pharmaceutical products and remedies, a result of the thriving - and global - patent medicine and cosmetic industry in nineteenth century America.

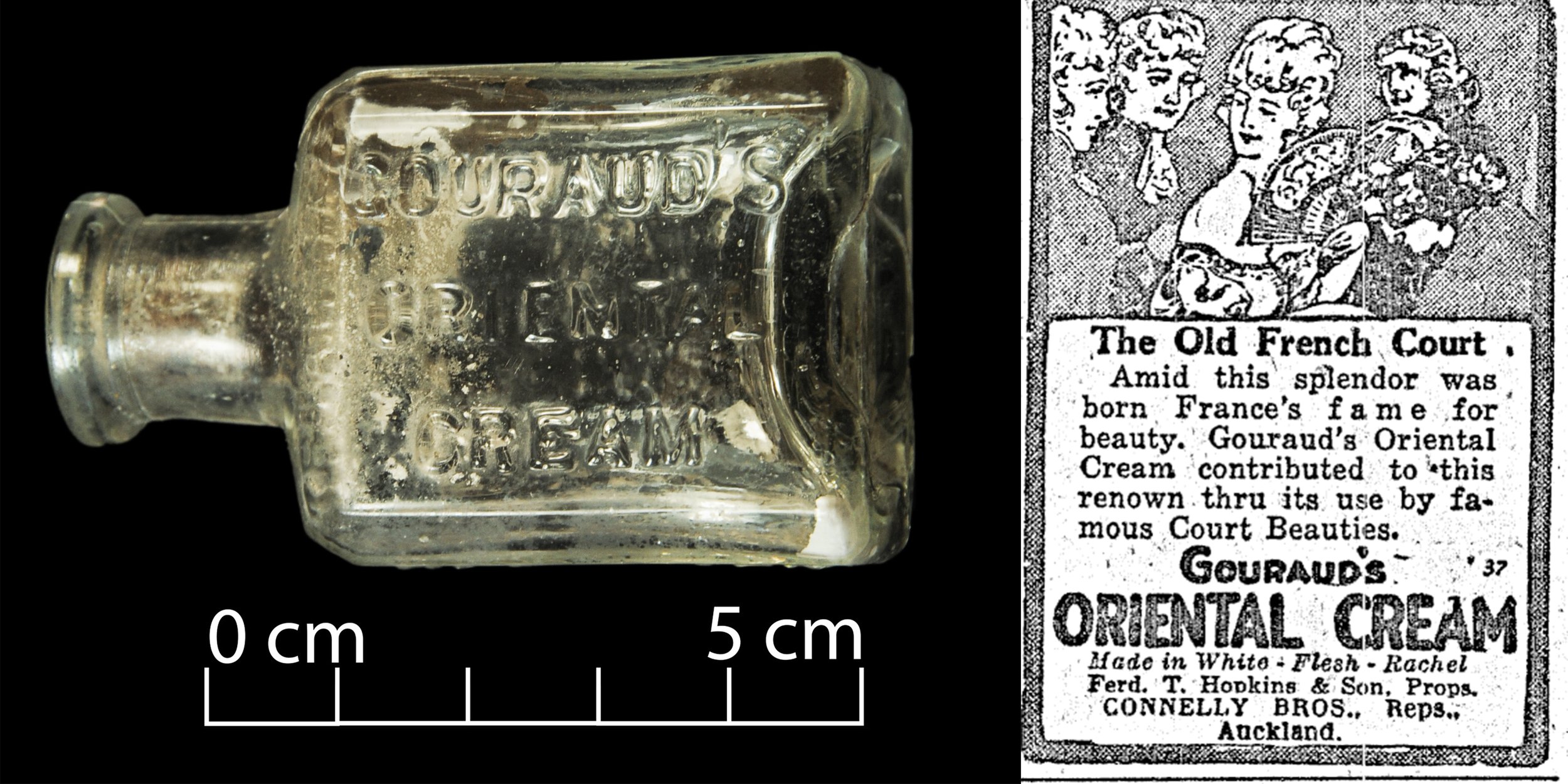

First up, Gouraud’s Oriental Cream. Despite the name and the advertising, this was an American product, created by Dr F. Felix Gouraud, a.k.a Englishman Joseph W. Trust, an immigrant to the US in the 1830s. Trust was a bit of a hustler, who went into the patent medicine business and reinvented himself a few times, eventually landing on “Trust Felix Gouraud” or “the Doctor”. He died in 1877 and his business was continued by his third wife, Martha, and, eventually, her second husband, Ferdinand T. Hopkins. Surprisingly, the most interesting thing about Gouraud’s Oriental Cream was not the somewhat chaotic life-story of its creator, but the fact that the cream contained mercury. Used as a skin cream - and advertised as a ‘safe’ remedy for brightening the complexion - the product contained enough mercury to actually cause poisoning in some users, defying the marketing claims that it was “so harmless we taste it to be sure it is properly made”. Despite this, it continued to be made and sold into the 1930s, long after the harmful effects of mercury were known. Image: J. Garland; New Zelaand Herald 11/04/1927: 7.

Barry’s Tricopherous has long been one of my favourite artefacts, due to the completely outlandish claims made about its effects and the actual contents of the product. Alexander Barry of New York was another purveyor of patent remedies, although his success was more in the realm of haircare. His Tricopherous, first sold in the US in the mid-19th century, was marketed as a hair restorative with the extraordinary power to also “cure eruptions and diseases of the skin” and “heal cuts, burns, bruises and sprains”. The remedy was actually mostly alcohol, making it unlikely it would do even half of what it promised. Despite this, Barry’s Tricopherous - and other Barry’s products (including hair dye) - remained very popular. Barry’s Tricopherous is one of the most common haircare products found on 19th century sites in Christchurch. Image: J. Garland; Otago Daily Times 23/11/1871: 4).

Murray and Lanman’s Florida Water is another fairly common 19th century product, a perfume or “eau de toilette”, which sounds so much better than the English translation “toilet water”. Murray and Lanman were also based in New York and their Florida Water, an American alternative to the European ‘Eau de cologne’, became famous around the globe during the 19th century, to the point that the company was involved in several court cases to protect their trademark. The name came from an early 19th century mythical association of Florida with the fabled “Fountain of Youth”. The fragrance is still sold today and, as a side note, is mentioned in Gone With the Wind, perhaps an indication that it was one of those products whose ubiquity sees them absorbed into the cultural landscape of their time. Image: J. Garland; New Zealand Times 20/12/1884: 4.

Weston’s Wizard Oil is easily a contender for the best patent medicine name of the 19th century, although it is maybe not a name that inspires trust in its efficacy. Marketed as the “Great American Medicine”, Weston’s Wizard Oil was one of those “cure-all” patent medicines that claimed to fix everything with its combination of “healing gums, balsams, vegetable oils and rare medicinal herbs”. My favourite is the promise to “raise the bedridden”. Weston’s Wizard Oil was the brainchild of Frank Weston, a showman (he briefly ran an Opera House) who combined entertainment with marketing his patent medicines. Weston was American by birth, but spent a great deal of time in Australia, touring his Wizard Oil and Magic Pills, as well as his other ventures (see Foxhall 2017 for an interesting discussion of Weston’s career and attitudes in context of race and quarantine in Australia).

Finally, to prove that not all of the American artefacts in the collection are patent medicines, perfumes or cosmetics, here is an example of one of the most famous American brands of the last 200 years - Heinz. This olive jar, which still has a little bit of the label remaining, is a 20th century artefact, dating to the 1920s, but Heinz has its origins in the 1860s with Henry J. Heinz of Pennsylvania (Lockhart et al.). They famously marketed their “57 varieties” of pickles and sauces from the 1890s onwards, including the stuffed olives represented by this jar. Image: J. Garland; Evening Star 10/09/1935: 14.

Jessie Garland