On windows

These days, in Aotearoa, we expect a house to have windows. While this has by no means always been the case across cultures or throughout time, it was the expectation of the European colonial settlers who arrived in Christchurch in the 19th century. Conveniently for a buildings archaeologist (or anyone else wanting to work out when a house was built), not only were windows ubiquitous, they’re also quite useful for helping you work when a house might have been built. Caveat, though: all the dating information that follows is specific to Christchurch. These dates might be the same or similar for other parts of Aotearoa, but I don’t know that for sure. For other places, they might at least provide a useful starting point, or a rough indication. Which leads me to another caveat: I’d never recommend relying on just windows to date a house – I think of dating a house as a bit like a process of triangulation, as it relies on a range of sources.

Images of houses in Lyttelton and Christchurch from the 1850s and 1860s show that houses had either casement or sash windows, and at times, it’s quite hard to tell which. It’s also hard to know which type was more common in these decades – in the sample of 101 houses I analysed for my PhD, three of the four houses built during this period had casement windows. But, when you start looking at newspapers from the period, advertisements that mention sash windows were nearly ten times more common than those that mentioned casement or French windows (as they were also known).

A casement window. Casement windows (also known as French windows) hinged on the side.

A four-light sash window, formed from two sashes, one above the other, that slide up to open. Note the small horns or lugs at the base of the upper sash (& read on to find out more about them!).

By the 1870s, though, sash windows were the most common type of window used in Christchurch houses. In fact, they were pretty much the only type used in new builds, if the results of my analysis can be relied on (and I like to think they can). They would remain as such until the early years of the 20th century. Which brings me to my first dating tip.

Dating tip #1: if your house has (original) casement windows, it was built in the 1850s/1860s, or in the early 20th century – they come into vogue again c.1910.

Sash windows were available right from the outset of the colonial settlement of Lyttelton and Christchurch. More than that, sash windows were being made here from the 1850s. It’s perhaps more accurate to say that they were being assembled here from that time. As well as people advertising that they were making sash windows, there were advertisements in the paper for window glass (and glass putty), and people may have been making the frames here from scratch, or may have imported the frames/frame components and then added the glass. Why this would be, I’m not sure, but it may have reflected the potential for windows to break when shipped here.

R. C. Bealby, covering all the bases by selling glass, putty and sash windows in 1850s Lyttelton. Image: Lyttelton Times 22/2/1851: 1.

In the period between 1850 and 1900, sash windows changed in a couple of key ways. Firstly, there was the number of panes. The earliest sash windows had numerous small panes (or ‘lights’). I’m not sure at what point the four-light sash window (the sash window shown above is a four-light window, having two lights in each sash) becomes most common, as there weren’t enough pre-1880 houses in my sample to draw any firm conclusions about this. But I can tell you that standard-sized two-light sash windows begin to appear in the late 1870s (there’s a smaller type around earlier on), and were the predominant type by the early 1880s.

A two-light sash window, with just a single pane of glass in each sash. Unlike the four-light sash shown above, there are no horns on the upper sash in this example.

Dating tip #2: If your house has four-light sash windows, it was probably built before c.1885. If it has two-light sash windows, it could have been built any time from c.1875 and was almost certainly built after c.1885.

The other change in sash windows occurred at around the same time (although not always on the same windows). This was the appearance of horns (or lugs) on the upper sash. Most sources suggest that these horns fulfilled a structural purpose: as the glass panes in sash windows increased in size (which happened as the number of panes decreased), horns were added to the upper sash to improve the strength of the corner joint and better support the weight of the glass (Sash Window Restorations, 2023). Like two-light sash windows, sashes with horns first appeared in Christchurch in the late 1870s, but were not common until the early 1880s. Windows without horns did persist, however.

Dating tip #3: well, it’s much the same as #2 – if your house has sash windows without horns, it was probably built before c.1885. If it has windows with horns, it could have been built any time from c.1875 and was almost certainly built after c.1885.

Of course the adoption of technology never quite works in a nice, orderly chronological fashion (and, let’s face it, if it did, it would be so much less interesting – although easier): you will find sash windows with two-lights and no horns, and others with four-lights and horns (as in the examples shown here). You’ll also find houses from the 1890s with four-light windows, and houses from the 1860s with two-light sash windows (but these tended to be a narrower form, not the dimensions that were common by the late 19th century). Old forms persisted, building elements were reused, fashion worked in peculiar ways and there were always early adopters.

This house was built by Harriet and John Snell in c.1899, but had two-light sash windows (with horns). John was a dealer and in 1897 he was advertising the sale of building materials from the recently demolished Central Hotel, including sash windows (Star (Christchurch) 9/9/1897: 3, 17/11/1897: 3). The Central Hotel was extant by at least 1863 and would not have had two-light sash windows (Lyttelton Times 29/7/1863: 3, 20/4/1865: 6). It is possible that the sash windows in the house at 558 New Brighton Road came from that hotel. Image: K. Webb.

But wait, there’s more! Yes, there’s another way that windows can help us date when a house was built: the shape of the bay window. Think of bay windows as having three main forms: splayed, rectangular and octagonal. Photographs indicate that rectangular bay windows were not unusual in the 1850s and 1860s, particularly on houses built in the Gothic style (which often had the aforementioned narrow sash windows). In the 1860s and 70s, though, the splayed bay was the predominant type, with the rectangular bay appearing again in the early 1880s, and quickly becoming the most common form. In Christchurch, it seems as though it wasn’t until the late 1890s that the octagonal form was used (although I know this form was introduced earlier in the 19th century elsewhere in New Zealand).

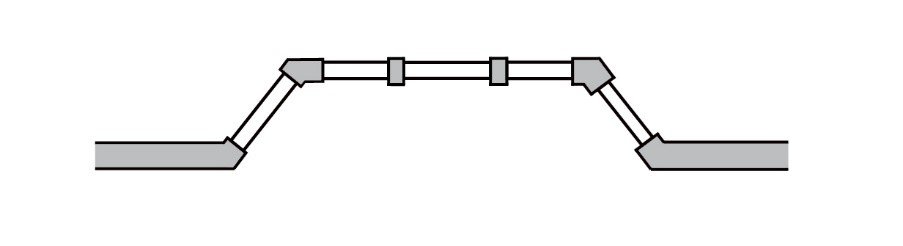

Plan view of a splayed bay window.

Plan view of an octagonal bay window.

Plan view of a rectangular bay window.

Dating tip #4: Splayed bay windows? Probably built in 1860s or 1870s. Rectangular? Probably built in the 1880s or 1890s (but perhaps the 1850s or 1860s, although these are of a somewhat different shape than the later ones). Octagonal? Late 19th or early 20th century.

Before I finish, I want to squeeze in a couple more window titbits. No one, I am sure, will be surprised to learn that, the more windows a house had, the wealthier the occupant is likely to have been. There’s a certain irony to this because, also, the more windows, the colder the house no doubt was. Clearly, if you were wealthier, you probably had more fireplaces, but there were only so many you could have, and those 19th century fireplaces only put out a certain amount of heat – and that wasn’t much, regardless of how wealthy you were. Windows also came in varying sizes, at varying prices. But there’s another way that wealth came into play. Most rooms only had one set of windows. Of course, it was only possible for rooms on the corner of a house to have more than one set of windows, but it was only in the homes of the wealthy that this was likely to have been the case. The majority of corner rooms just had the one set.

The cost of sash windows in New Zealand, 1883. Source: Leys 1883: 724, 728, 730.

Windows, then, like halls, are one of the components of a house that can tell you more about a house than you might have first thought. They’re perhaps a little more ‘practical’ than halls in that regard, being able to help us work out when a house was built – although they also have insights to offer in terms of wealth and class. Stay tuned for a future post on doors…

Katharine Watson

References

Leys, T. W. Brett’s Colonists’ Guide and Cyclopedia of Useful Knowledge: Being a Compendium of Information by Practical Colonists. Auckland: H. Brett, 1883.

Lyttelton Times. Available at: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers

Sash Window Restorations, 2023. “History of the Sash Window: Part 3.” Sash Window Restorations. Accessed 7 September 2023. Available at: https://sashwindowrestorations.co.uk/history-of-the-sash-window-part-3/

Star (Christchurch). Available at: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers